Robert Vermeulen

23/05/2024

It was more than 15 years ago that I last gave an online opinion on a cricket-related topic, at the time regarding identification of players during games following a few then recent incidents in which teams had fielded players under false or fake names. A mildly controversial matter at the time. I would now like to express my opinion on a more fundamental issue that will hit a few more nerves within our small community. I avoid naming names in this piece as that would not be right, but every person who has a more than fleeting knowledge of the Dutch cricket world can come up with their own examples.

Introduction

This piece was brought on by a quote from my friend Rod Lyall in his piece of 21 April 2024 for this website:

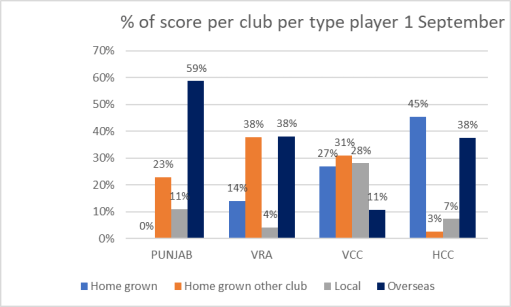

For the first time in the 134-year history of the Dutch competition, more overseas-produced players took the field in top-flight games than those who had learned their cricket in the Netherlands – the actual figure was 57%.

This remarkable statistic is perhaps skewed a little by the fact that three teams did not play, the triple-header at Thurlede having been called off on Friday night after a week of heavy rain, but nevertheless the trend is clear: the leading Dutch clubs are relying ever more heavily on imported players in their quest for silverware.

Of the seven teams who did play, only three fielded a majority of Dutch-produced players, and one, Salland, actually put out a side without a single member who had learned their cricket in this country.

What are we talking about?

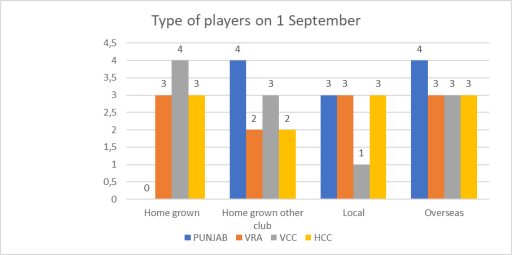

For the sake of clarity I would like to present you with a few definitions. When I speak of local players, I mean those players that are either home-grown players or are players that are here for other reasons than cricket. This last group are those that moved here for work, study or other non-cricket related reasons like marriage/relationships/family reunion or refugee status. Home-grown players are players that learned their cricket here. Overseas players are players whose main reason for being in The Netherlands is to play cricket. There are ample examples of hybrid situations or evolving situations. The fact that I bumped into Lindon Joseph (former WI and Gandhii (Dosti) fast bowler) last year, shows that some former overseas players can end up very local players in time. Great to see one of the all-time greats still in action!

Players with a Dutch passport (like in the Dutch XI) who are non-local players, are overseas players. For the purpose of my argument, their nationality is a coincidence.

I have been told multiple times that certain overseas players are not paid by the clubs or just small amounts for coaching etc. That is not the point. The reason why overseas players come over to play in The Netherlands is irrelevant for this discussion. It might be relevant to the debate about the allocation of limited funds within the Dutch cricket community. That is a matter for a different day.

Points system

I must point out that, during my stint within the KNCB Board, the Bureau, Rod and myself did look into a system to regulate the influx and use of overseas players. For me the main reasons for that would be:

- to stimulate the development and use of home-grown players, especially junior players;

- to prevent the (further) escalation of the perceived necessity for overseas players to either prevent relegation or ensure championships;

- to create a level playing field for clubs, whereby long term success is not determined by the depth of the pocket, but by the quality of the club structure.

We had a look at the Victoria (Australia) ‘points method’ whereby teams were only allowed to field a maximum amount of 24 (player) points per match. Based on their status (home-grown by the club, home-grown, local or overseas) players are allotted a certain amount of (player) points. Home grown-players would count for 1 point, but test players for 7, with many variations in between.

We played around with a few KNCB specific variants at the time, but it never really caught on. The last version was produced in October 2020. I re-read it and I still feel that it has significant merits, not in the least as a basis for a more fundamental discussion about our collective future as a cricketing nation.

Lets be brutally honest. The number of clubs that can say that they have a plan to create their own home-grown player pool can be counted on the fingers of one hand, maybe two. One only has to look at the current junior competitions to see which Topklasse and Hoofdklasse clubs are absent in most of the age groups. There is no natural succession there. Those clubs will have to rely on either an influx from within the current local player pool or procurement of overseas players.

Would a point based system be legal?

In the past we played around with a few types of systems to limit the amount of overseas players in our top leagues. The most recent regulation limiting the amount of overseas players was (long) upheld by a mutual understanding between the clubs. The most potent legal point against this regulation was not EU regulation, but the Dutch Wet Gelijke Behandeling (the Equal Treatment law). One cannot make any distinctions between people based on nationality. It was because of that the regulation was scrapped and never replaced by anything other than the players list requirement.

The points system would, in my humble opinion, not be problematic as it categorises players based on their (cricketing/club) status and only places a restriction on the team total. Everybody as an individual can play, the club must balance their points per match.

Make or buy?

The player-tombola we saw this winter was a nice example of destructive forces at work. 20 years ago, when I chaired HCC, we would receive calls from players after every season to see what ‘deal’ they would be able to get. We never were interested. This type of players is notoriously fickle. At the time it was only a small group of nomadic players.

Now it is worse. The rumours were rife this winter of whole groups of players hawking their services to the highest bidder. Everybody was talking to everyone it seemed. Even players that one would regard as ‘club people’ were clearly willing to hop around.

Just like in business the question is clearly: Make of Buy? Most clubs can’t make, so they buy. I suggest to you that this will be our collective undoing in the long run. Both for the clubs and for Dutch Cricket.

Recent growth

It is not only doom and gloom though. In the last few years we have been blessed by a significant increase of local players, mainly from India. This means that the sport grows. That is really great on the face of it, but will be highly dependent on the stability of growth. Will these players, especially the juniors that rise through the ranks, permanently commit to Dutch cricket?

For now we must enjoy the broadening of our players base and welcome all to our fields. We can even see a few local players, non-home grown, playing in our top leagues. It is early days.

Topklasse / Hoofdklasse

The more pressing issue is that of the population of our top leagues. As stated, the clubs compete for a very limited amount of local players. Apart from the usual journeyman players who have no clear club affiliation at all, I was shocked to see a few transfers of some real club people. This is a zero-sum game, whereby the gain of one club is a real loss for the other. This hurts clubs. If this happens at junior level, it is even worse. If, as a club, you invest effort and resources in building a junior program and juniors are constantly poached by clubs that put in less effort, you undermine the future of the whole community. What is the point of putting in the effort when others can just wait until you have produced a ‘poach-able’ player? These centers of youth development should be protected and cherished.

And then there is the issue of what I have coined ‘the bank accounts with a first team’. The only apparent current reason for their existence is the survival in a certain league. It is an empty shell for the rest. There is no junior development, hardly a club structure and most definitely no long term strategy other than: next year we will still play at this level. What is the point? If the bank account runs out of funds, the team vanishes. There is no added value to the long term development or even survival of our Game. It can even be argued that it damages the Game. A championship is meaningless if you can simply buy it. It is nice to boast that you were champions, but lets be honest, what is the point if you implode like a soufflé after that.

I understand that the introduction of overseas players has on the one hand beneficial effects on the level of play, but, on the other hand, could take the place of a home-grown player that would like to play and evolve. We need the home grown and local players for the long term. They are the ones that will play when the pro is not available, they will play second XI, they are the parents of the next generation. They are the club.

A junior who feels or knows that he/she can (and will) be replaced by any overseas player in a blink of an eye, might lose their motivation and stop competing. It is potentially utterly corrosive.

Nederlands XI

The Dutch XI has done very well the last few years and we were all delighted to play on the big stage. But, apart from a few home-grown players, most of the players are overseas players (with a few hybrid players). The current success is not necessarily the result of an increase of level of play within The Netherlands. The current group is very talented and has shown ample character. It is certainly not a matter to take for granted; Cricket is a funny game.

Strong clubs

I have previously advocated that our local cricket community will only survive when we have healthy clubs with healthy long-term goals. The current situation just thinly papers over the big cracks. It is a truly fragile situation. We need to extend the pool of local players, preferably through long-term growth.

The French situation with regard to phantom Women Cricket leagues shows how risky rules could be to make youth or women teams mandatory in order to play top cricket. Although I was previously in favor of such ideas, this made me reconsider a bit. A better first step could be regulations to promote the direction of limited resources towards better choices, like home-grown players.

We need to turn the balance away from buy towards make. That can only be done by dis-incentivizing buy by introducing a system whereby clubs are rewarded for make. If you can’t field a team without exceeding the maximum, you might want to reconsider your future as a going-concern top cricket club in The Netherlands. Such systems would need an implementation period of a few years to give teams the chance to adapt.

I would like to call upon the members of the KNCB to consider a version of the points system and, even slowly, steer clubs back towards make. We can still turn the tide.

A lot of clubs are in some kind of survival mode, with a lack of active volunteers, constant financial issues, nonsense with their facilities and low member participation. Few shoulders bear most of the weight. An effort should be made to assist these clubs. That is a better way to spend your resources than trying to hang on to success that you know you cannot sustain in the long run.